Subtract today’s Union wages, pensions, health & welfare plans, vacations, night premium pay, holiday pay and today’s 40-hour week and you’ll have the conditions under which a handful of Food Industry clerks worked when they organized and gave birth to UFCW 588 In June of 1937.

Clerk’s wages in that far-off day were pegged at anywhere from $16 to $24 per week – when the workweek consisted of a minimum of 60 hours and many times stretched to 70 hours – at no increase in pay. Store Managers earned $25 – $30 per week and a vague promise of a “bonus.”

Contracts were nonexistent. Few stores had paid vacations, holiday pay, overtime; the five-day, 40-hour week was unheard of, and the conditions enjoyed in the Industry today were beyond the fondest dreams of the average Food Clerk. Other unorganized Retail Clerks fared better. Shoe Clerks, those working in variety and department stores and related fields, enjoyed better wages and conditions than did those employed in the Retail Food Industry.

Consequently, employment in the retail food stores was a sometime thing. Clerking jobs were taken only as a fill-in, while the employee waited for a better job. Turnover was high and the Clerks were unhappy with their lot.

Competition was keen. Cash-carry chain stores were just entering the field. As they did so, the service stores reached out in an attempt to hold their sales. War ensued. Prices dropped and so did the Clerk’s pay. Truly, Food Clerks in 1937 were the forgotten people.

In just a few days in June 1937, after prompting from the Retail Clerks International Protective Association and with the cooperation of Teamsters Local 150 Secretary Marty and his staff, a handful of Clerks got together, signed application cards, the International appointed a temporary, volunteer Secretary, and an organizing drive began.

Under the leadership of the unpaid Secretary, James F. Alexander, the drive moved steadily forward. Organizing was not too difficult, since the average employee hoped to better his lot, and in most cases, organizers were greeted with open arms.

Additionally, for the first time, workers had the beginnings of the benefits of the second F.D.R. (Franklin D. Roosevelt) Administration. The Wagner Labor Relations Act was now on the books and workers had little to fear with the new measure of protection against discharge or disciplinary action from unfriendly employers.

At the same time, related national activities had set the scene for increased action by workers and Labor Unions. John L Lewis had taken his mine workers out of the AFL and his action had prompted the AFL to step up its own organizing drives in the miscellaneous and unskilled crafts.

Working nights, Sundays, and during lunch hour, the small, dedicated group applied itself diligently to the task, and on June 21, 1937, the R.C.I.A granted a charter and UFCW 588 was born.

Within 60 days, about 250 workers had been initiated; and at the end of 90 days, the employers gave legal recognition to the fledgling Union on an Industry-wide basis.

Negotiations for a contract opened immediately. The first contract was completed and the effective date set as January 3, 1938. Simultaneously, the membership in late 1937 elected Brother Alexander to his first term as Corresponding-Financial Secretary and he resigned his position as Manager of a Lynn & O’Neil grocery store to work full-time for the Union.

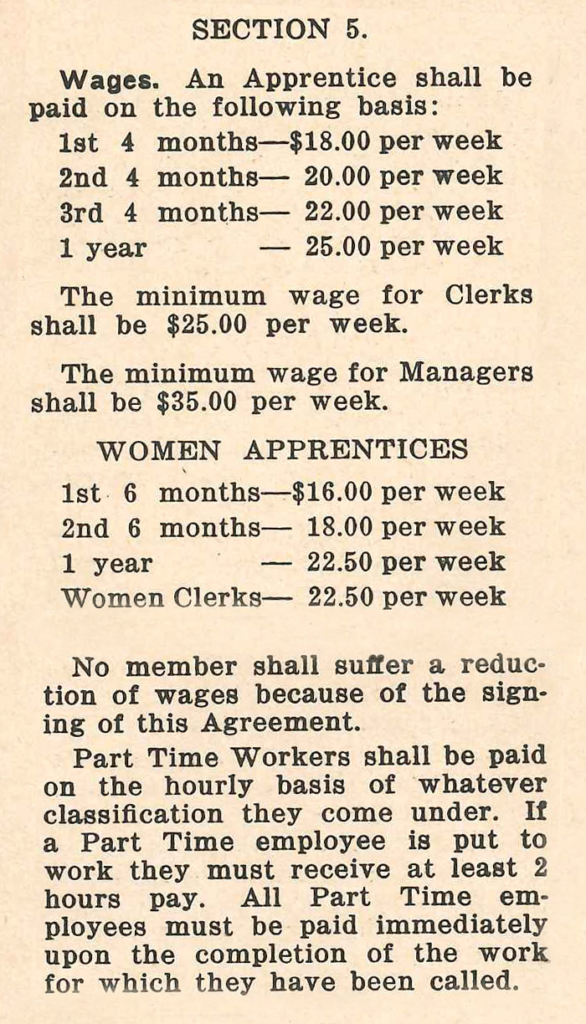

By today’s standards that first contract might well bring a smile to today’s member. But the wages and conditions guaranteed by that agreement were an important “first” for the members of that day.

For the first time the workweek was established. It would be, the pact said, a six-day week with overtime after nine hours a day, or 54 hours per week. This item alone cut from six to 16 hours from the employee’s workweek.

The contract called for a minimum weekly wage of $25.00 (46.5 cents per hour) for experienced male Clerks for a 54-hour week and $22.50 for experienced female Clerks for a 48-hour week. It also set the standard for Managers -$35 per week. One week’s vacation, with pay, after one year’s employment was also granted by the new pact. One of the better conditions established by the agreement was the clause governing store hours. Stores could not open before 7:00 a.m. and they must close by 8:00 p.m. – but more Important, the stores were required to close on Sundays and holidays!!!

These closing hours, while one of the finest provisions of the contract, almost proved to be the downfall of the Union. By the middle of 1938, even with members serving as volunteer pickets on Sundays, UFCW 588 was spending almost $1,000 weekly in an attempt to keep the stores closed. The Union’s books were beginning to show a generous sprinkling of red ink.

After weeks of friction regarding these closing hours, the employers asked for meetings which finally resulted In the Clerks trading store hours for Sunday and holiday premium pay.

The next three years were lean indeed, and the Union had been able to raise wage rates only $5.00 per week over the period. In 1942, after a deadlock in negotiations the Union struck two chains on a Saturday morning and on Monday other employers locked their employees out. On Wednesday of that week the contract was settled and the strike was over, with Clerks receiving a $5.00 per week increase. This was as much as they had received in the last three years. The strike and lockout had lasted only five days and the victory was sweet.

But the victory brought more than just an increase in wages. It proved that the organization was a living, potent force and that the Clerks would stand up and fight for their conditions when the chips were down. The victorious settlement of the first and only Industry strike in Sacramento in the history of this Union brought with it the respect of the members, the employers, the entire labor movement, and the public as a whole.

During the years of World War II, UFCW 588, as did all Unions, accepted the law of the land and entered into a no-strike pledge, agreed to the wage freeze and learned to live with the rules and regulations established by the War Labor Board. Under such conditions, little progress was made. The workweek, however, was cut from 54 to 48 hours, after months of effort, through the filing of briefs and numerous hearings by the Board. But with the cut came a reduction in pay from $35.00 to $33.00 per week. When the war ended and the War Labor Board expired, UFCW 588 started moving again.

1945 brought a $7.00 weekly wage raise, pegging Clerk’s scale at $40.00. Since 1945, weekly wages have risen steadily to bring today’s weekly scale for Journeyman Food Clerks to $763.20 while the workweek was reduced from 48 to 40 hours.

UFCW 588’s jurisdiction has grown through the years, through normal organizing activities as well as through mergers. In 1941 Roseville Local 964, desperate after five years of stalemate, moved to merge with 588 and in a short time, Roseville Food Clerks were on par with their brothers and sisters in Sacramento.

The R.C.I.A. chartered a textile Local 1637 in Sacramento in 1950, covering workers in department stores, dress shops, and variety stores, but after an effort of about one year’s duration, that Local also merged with 588.

In 1953, Modesto Local 1273, faced with a dilemma, entered into meetings with UFCW 588, which resulted in a merger after due consideration and voting by both Union bodies and approval by the Retail Clerks International Association.

Local 197 covering San Joaquin County and headquartered in Stockton merged with UFCW 588 in 1983 with overwhelming approval of their respective memberships.

In December of 1984, the Executive Board of UFCW 588 asked Jack L. Loveall, International Vice President and Director of UFCW Region 14, to be the President of UFCW 588. Under the direction and leadership of President Jack Loveall, UFCW 588 immediately instituted a very aggressive organizing program which has resulted in an ongoing increase of 588’s membership.

March 1,1989, Local 916 whose jurisdiction covered Butte, Colusa, Glenn, Lassen, Plumas, Sierra, Sutter, Yuba, Modoc, Nevada, Shasta, Siskiyou, Tehama, and Trinity Counties, merged with UFCW 588 to become the largest UFCW Union in Northern California and the third largest UFCW Union in the State of California – over 15,000 members strong.

The pioneering for the Union was done, almost in its entirety, by Food and Liquor Clerks who reaped many of the benefits of belonging to a growing, vital organization. However, in recent years the Union signed agreements with drug, department, variety, florist, hardware, and specialty shops which have brought appreciable gains to the members employed in these fields.

Recent mergers and undoubtedly the most historic mergers in Northern California became effective March 1, 1991, when UFCW Local 498, a meat cutter Local with 1,600 members, merged with UFCW 588-Northern California.

On June 1, 1992, Local 532, a meat cutter Local Union representing 1,000 meat cutters in Napa, Solano, and Contra Costa County, joined forces with UFCW 588. Then, on October 1, 1992, UFCW 588 expanded its jurisdiction to the California coast with the merger of UFCW Local 1532, representing almost 3,000 members in Sonoma, Lake, and

Mendocino Counties.

The next significant merger occurred on August 1,1993, when UFCW Local 127, representing 2,800 Retail Meat and Food Processing members in San Joaquin and Stanislaus Counties, merged with UFCW 588, bringing the membership to 27,000 strong.